Others continued to find their way to the growing community, some of whom were the Browns, Burlesons, Grants, Greens, Henrys, Hunts, Jones, McKinnons, Nunns, Perpeners, Sanders, Warrens, Winkfields and Usserys.

Others continued to find their way to the growing community, some of whom were the Browns, Burlesons, Grants, Greens, Henrys, Hunts, Jones, McKinnons, Nunns, Perpeners, Sanders, Warrens, Winkfields and Usserys.FAYETTE COUNTY, TEXAS

A Footprints of Fayette article by Carolyn Heinsohn

Located eight miles west of Flatonia in southwestern Fayette County near the point where Gonzales, Lavaca and Fayette Counties meet, the Armstrong Colony is one of two freedmen’s settlements in the county. The other community is Cozy Corner, which is located at the intersection of FM 155 and Co. Rd. 3233, approximately five miles south of La Grange.

Freedmen’s settlements, which primarily were formed in the eastern half of Texas in the years after Emancipation, were informal, independent rural communities of freed African-American landowners and land squatters, who were predominantly farmers and stockmen. These settlements, which were sometimes called “freedom colonies” by the African-American settlers, were somewhat of an anomaly in Texas after the Civil War where white elites rapidly resumed economic, political and social control, and sharecropping became prevalent in the agricultural system that previously had been based on slave labor.

The formation of these independent black communities was motivated by the freedmen’s desires for land, autonomy and isolation from the whites. Even though the 1865 rumor that the federal government would provide all ex-slaves with “40 acres and a mule” proved to be false, a minority of the freedmen set out to achieve that dream, and some of them succeeded in establishing themselves on pockets of wilderness, cheap land, or neglected land previously little utilized for cotton production. The majority of the freedmen, however, took employment with white landowners as day laborers, sharecroppers or share tenants.

Some of the slaves were actually freed prior to Emancipation for a variety of reasons. Occasionally, a white plantation owner would free his mulatto progeny and their slave mothers. Whether freed or not, certain favored slaves were given the privilege to work in the plantation house and were sometimes allowed to learn to read and write. Perhaps this exposure to a different world other than fieldwork and heavy labor, plus the opportunity to receive a rudimentary education, planted the seed that then germinated after Emancipation, providing the impetus for some of the freedmen to venture away from their plantation locations. They sought a new life that they hoped would offer far greater opportunities for their families than what was available to them at that time. Plus, they understood that education was a tool to effectively function in a literate society, so oftentimes they supported the early establishment of schools in their new communities.

The founders of the Armstrong Colony were among that minority group, who took the risk to re-locate and had the fortitude to seek a new life in a community that they themselves created. Although it was un-platted, unincorporated and never had its own post office, the Armstrong Colony was unified by a church, schools and several scattered businesses.

One of the first to arrive in the area was the family of Jacob and Eliza Armstrong with their four children. The 1870 census lists them as first living in Precinct 3 in Lavaca County. Enumerated were Jacob, a farmer, age 52, born circa 1818; Eliza J., age 45, born circa 1825; Mitchel, age 25; Rachel, age 20; Frank, age 17; and Sarah, age 15. More than likely Jacob was a sharecropper.

According to family tradition related by a descendant, Felton Armstrong, the Jacob Armstrong family came to Texas in 1865 from Lafayette, Louisiana. However, the 1870 census records indicate that Jacob was born in Mississippi. His wife, Eliza, and children were also born in Mississippi, although records indicate that Eliza’s parents were born in Alabama. Perhaps the entire family was sold to a Louisiana plantation owner, so they were forced to move to Lafayette sometime before their emancipation and subsequent move to Texas.

One of Jacob’s neighbors in Lavaca County in 1870 was Sam Bilton, born circa 1842 in Tennessee, and wife, Charlotte, born circa 1848 in Missouri, along with their five children. Another child was born later in 1870 after the census was taken. Peter Grant, age 28 from Louisiana; his 20-year old wife, Ann, who was born in Mississippi, and their three young children were living nearby, so probably were working on the same land. They would later become neighbors again in Armstrong Colony.

In December, 1875, Jacob Armstrong purchased 162 acres of land on the head waters of Peach Creek in Fayette County, approximately 25 miles southwest of La Grange, from G.C. McGregor and E.H. Fortran for $755.00. He paid $5.00 down with five promissory notes of $150.00 each.

In the 1880 census, Jacob, age 63, was listed as living in Precinct 6 of Fayette County in the area that is now known as Armstrong Colony, along with his second wife, Louise, age 62; daughter, Rachel, age 29; widowed daughter, Selena/Sarah Garrett, age 26, along with her six children, and three grandchildren. Jacob’s sons, Mitchel and Frank, and their families were also living on his property. Mitchel (1843-1904) married Fanny Bilton (1854-1939), daughter of Sam Bilton, possibly before moving to Fayette County. In 1889, Jacob sold 82 acres of his farm to his son, Mitchel, for $100 and a promise that he would pay one-half of the unpaid balance on the notes for his original 162 acres, probably because Jacob was unable to pay for the notes on time. He also sold 14 acres to his grandson, Ellard, for $50 and a promise to pay one-fourth of the unpaid balance on his notes. Ellard was able to purchase another 16 acres that were located adjacent to his grandfather’s property from McGregor and Fortran for a total of 30 acres.

Actually, the first freedmen family to move to the area that became Armstrong Colony was Harry Simms (1848–1911), born in Texas, the son of Brutes and Ferberry Simms, and his mulatto wife, Ellen Pettit, (1845-1927), daughter of Harvey and Adeline Pettit, and their children.. The parents of Ellen Simms were either from Arkansas or Tennessee, but were living in Gonzales County when they sold 100 acres of land on Peach Creek to their daughter and son-in-law, who also were living in Precinct 3 of Gonzales County, for $160 in July, 1874. The 1900 census indicates that Harry and Ellen had been married for 34 years and had nine living children. Although Harry’s tombstone indicates that his birth year was 1839, several documents indicate that he was actually born circa 1848.

The Frank Derry family moved into the community after the Armstrongs. In March, 1877, Frank Derry and his wife, Mariah, purchased 102 acres approximately 30 miles west of La Grange from N.W. Brown for $500. In the 1880 census, Frank Derry, born circa 1827 in Alabama, was shown to be living in Fayette County with his mulatto wife, Maria, born circa 1832 in North Carolina, and their nine children, a nephew and a niece. One of their daughters, Clemmie, was married to Emmette Simms, the son of aforementioned Harry and Ellen Simms.

Frank and Mariah later purchased an additional 100 acres on the waters of Peach Creek. They eventually sold 30 acres from each of their tracts of land to their two sons, Alex and Charley, plus another 34 acres to A.B. Kerr of Muldoon. By 1899, Marie had died, and Frank, age 71, married Melindy, age 55. In 1900, he was living in Armstrong Colony with a mix of children, grandchildren and a step-grandson. By 1910, Melindy must have died, because she was not enumerated in the census, and Frank was living with his daughter, Clemmie, her husband and their eight children.

The Sam Bilton family is also documented as one of the early families of the community. Sam purchased 150 acres on Peach Creek in the Menefee League from John Cline for $1200 in November, 1889. He had three unassigned promissory notes for $400 each; however, he was unable to pay the notes, so he was forced to sell his land and have the notes assigned to T.M. Connon of Flatonia. However, Bilton’s three sons, Sam, Jr., A.B. and William, agreed to collaboratively pay the notes in order to keep the family land.

Others continued to find their way to the growing community, some of whom were the Browns, Burlesons, Grants, Greens, Henrys, Hunts, Jones, McKinnons, Nunns, Perpeners, Sanders, Warrens, Winkfields and Usserys.

Others continued to find their way to the growing community, some of whom were the Browns, Burlesons, Grants, Greens, Henrys, Hunts, Jones, McKinnons, Nunns, Perpeners, Sanders, Warrens, Winkfields and Usserys.

The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, that was established by Congress in 1865, provided relief to the thousands of refugees, black and white, who had been left homeless by the Civil War. Many blacks turned to the agency for protection, advice or help in finding lost relatives. Although the Bureau was dissolved in July, 1870, it was most successful in Texas with its educational efforts. It helped establish 150 schools in the state with an enrollment of over 9,000 students. Perhaps, the Bureau influenced Jacob Armstrong and other nearby freedmen to establish a school for their children on Armstrong’s land soon after his purchase. The “school” was actually a brush arbor that had seats hewn from logs. Inclement weather would have been a definite factor influencing school attendance, but at least there was an effort to educate the children in the community, which was named after Jacob Armstrong, since he provided the land for the school and eventually the church.

Jacob Armstrong’s son, Frank, who married Clara Washington, was one of the first deacons of Armstrong Colony’s newly-founded Mt. Olive Church, along with Sam Bilton. The church, which was founded under the direction of Professor and Reverend O.E. Perpener, the first teacher and pastor, was organized in 1876 in the brush arbor that was serving as the “schoolhouse”.

The history of the church states that there were eight persons in the first church organization – six members of the Armstrong family and Rev. Perpener and his wife. As others moved into the area, they soon were sending their children to the school and attending the open-air church, which became the social center of the community. At first the church members met for prayer meetings on Wednesday nights, being called to worship by Jacob, who would blow a cow horn when it was time to meet. Light was provided by bottles filled with kerosene that burned with wicks of flannel rags. The church, which became known as the Mt. Olive Missionary Baptist Church, was eventually moved to a log cabin where services were held, and school was taught. An active Mission Society was later founded by the women of the congregation.

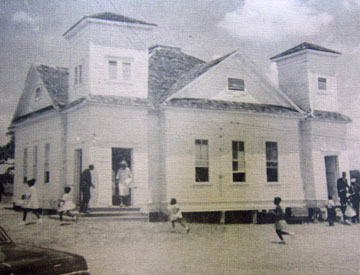

In 1914, Rev. F.D. Davis, a young dynamic minister, accepted the position of pastor of Mt Olive. Under his direction, the Baptist Training Union and a youth group were organized. He also launched a building program to create a new church building, which was completed in 1918 on an acre of land donated by Fannie Armstrong and Charlotte Bilton. That church, which had an interesting architectural design, was eventually in need of restoration, but instead it was razed and replaced by the present brick sanctuary in 1994. A fellowship hall stands nearby, and the Mt. Olive Museum and Cultural Center filled with historical documents, photographs and memorabilia of the community is located in the old “teacherage”, a structure that housed black teachers during segregation.

In 1914, Rev. F.D. Davis, a young dynamic minister, accepted the position of pastor of Mt Olive. Under his direction, the Baptist Training Union and a youth group were organized. He also launched a building program to create a new church building, which was completed in 1918 on an acre of land donated by Fannie Armstrong and Charlotte Bilton. That church, which had an interesting architectural design, was eventually in need of restoration, but instead it was razed and replaced by the present brick sanctuary in 1994. A fellowship hall stands nearby, and the Mt. Olive Museum and Cultural Center filled with historical documents, photographs and memorabilia of the community is located in the old “teacherage”, a structure that housed black teachers during segregation.

At one time, there not only was a primary school in the community, but also a high school known as the Albrecht School, both of which prepared many young people for college educations and careers in all walks of life across the United States. By 1992, there were 27 descendants of the first families who had obtained their college education at Prairie View College. The total number of graduates from other collegiate institutions is not documented, but undoubtedly, these families valued the importance of an education for their children.

Although the church and school were the spiritual, educational and social centers of the community, the Armstrong General Store, Cue Bilton General Store, Marvin Brown Store and Needham Store provided the necessities for the local people during the era when there was a larger population in the area, and transportation to Waelder or Flatonia was difficult. There were two gins operated by the Winkfield and Derry families when cotton production was significant enough to necessitate their existence. The Derrys also had a broom factory. The only remaining evidence of the once-thriving, small community is the church-museum complex on Armstrong-Derry Road, a well-kept cemetery located a short distance away, and the residences of a few remaining families, some of whom are descendants of the original families.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, oil was discovered in the area, so some of the families were fortunate enough to benefit from the short-lived oil production before the wells went dry. For those families with land and retained mineral rights, the newest oil boom related to drilling in the Eagleford Shale will provide some much-appreciated future income.

The majority of the descendants of those strong, pioneering freedmen, who pursued their dreams and persevered in their labors to carve out a livelihood in a community that they created, have spread out like the branches of a mighty oak, but their roots are still in the Armstrong Colony. Many return annually every August for the community homecoming event to reunite with their families and reconnect to their special heritage.