David W. Breeding

David W. BreedingLA GRANGE, FAYETTE COUNTY, TEXASs

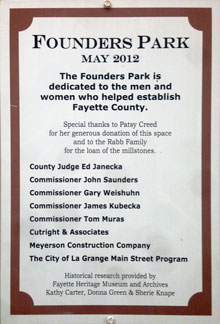

Founders Park is a pocket park located next to the Fayette County Clerk's office and across Colorado Street from the courthouse. The park was built in 2012 and dedicated to the men and women who first settled Fayette County. Kathy Carter, former director of the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives, profiled each of the founders for a series of memorial plaques that line the park's perimeter. These profiles were also published in 2012 as Footprints of Fayette articles in area newspapers.

David W. Breeding

David W. Breedingby Kathy Carter

David and Sarah Davis Breeding and five of their sons, John, Richard Landy, Napoleon Bonaparte, Fidelio Sharp, and Benjamin Wilkens Breeding came to Texas from Christian County, Kentucky in late 1832 and early 1833. The family settled along Cummins Creek near present day Willow Springs. Before the end of 1833 David Breeding’s four young nephews joined the family after the death of David’s widowed brother.

David and Sarah had a house full of youngsters who needed schooling but there were no schools in the colony. A log cabin on the Breeding homestead was used as a school house and a Mr. Rutland served as the teacher. David Breeding’s nephews attended as did the Alexander children, including Emily who later married Joel Robison. Jesse Burnam lived fifteen miles away across the Colorado River but brought his children to the school as well. He built a shed tent with a long bedstead for his daughters to sleep in while his sons slept under the trees.

Within two years of settling in Texas, the Breeding family found themselves in the middle of the Texas Revolution and four of the brothers served in the army in one way or another. Napoleon participated in the Siege of Bexar in December 1835 and he and John both served as Texas Rangers. Napoleon, John and Fidelio enlisted in the Texas Army but only Fidelio was on the battlefield at San Jacinto on April 21, 1846 serving under the command of Colonel Edward Burleson in the First Regiment, Texas Volunteers. Napoleon and John missed the battle because they were ill, possibly with the measles, and were detailed to guard the army camp. According to the pension application papers of Benjamin Breeding he served in the Texas Army and participated in an engagement at the Brazos River ferry crossing in San Felipe where a detachment of Santa Anna’s army was prevented from crossing the river. From there he was sent with his wagon team to help haul two cannons, the “Twin Sisters”, from Harrisburg to Sam Houston’s army. A few days before the battle he obtained a leave of absence so he could help his elderly parents and brother Richard flee during the Runaway Scrape.

Fayette County was created by an act of the Second Congress of the Republic of Texas on December 14, 1837 and the Breeding family served their new government in one way or another.

David Breeding was a member of the first Board of Land Commissioners, responsible for granting land to settlers and soldiers. He also served as a juror during the first District Court session. He died on December 28, 1843 and Sarah followed him ten years later. Both are buried at the Breeding family cemetery, five miles northeast of Fayetteville.

John Breeding was elected to serve as the first Fayette County Sheriff on January 1, 1838 and received his 1/3 league of land two weeks later. The first county jail was a wooden structure but it was not sufficient to confine prisoners so Sheriff Breeding boarded the prisoners out to local residents at great expense to the fledgling county. Breeding served as sheriff until 1840 and then served under Colonel John Henry Moore on a three month campaign against the Comanche Indians. He married in 1842 and had eight children. He died 1869 and is buried alongside his parents in the Breeding Family Cemetery.

Richard Landy Breeding was paid by the Republic of Texas for hauling lead for the government during 1837. On February 2, 1838, he received 1/3 league of land in Fayette County from by the Board of Land Commissioners. He married in 1844 and had at least 12 children. He was in the mercantile business for many years and lived near the Breeding homestead until he moved to Hays County in 1877. He was the last member of the Breeding family to own his father's, homestead which he sold in December 1877, reserving 1/2 acre referred to as the Breeding Family Grave yard.

Napoleon Bonaparte Breeding married Charlotte O’Bar on January 19, 1838 and it was the first recorded marriage in Fayette County. He also received his land grant of one league and one labor on his wedding day. N. B. Breeding served as juror during the first District Court session on October 22, 1838 and then as a member of the first Grand Jury. “Pole” Breeding was a member of the Snively Expedition in 1843. Napoleon and Charlotte had at least six children before he died in 1861.

Fidelio Sharp Breeding received two land grants for his military service to Texas during the revolution. In 1847 he sold his interest in his father’s estate to his brother Benjamin and joined the U.S. Army to serve in the Mexican War during 1848. Fidelio never married and died in 1849 in San Antonio while on his way to the California gold fields with his brother, Benjamin.

Benjamin Wilkens Breeding was only 16 years old when he participated in the Texas Revolution of 1836. His name appears on no official roster even though he did receive a land grant for his service and all the rest of his family participated. In 1840 he served alongside his brother John under Colonel John Henry Moore on a three month campaign against the Comanche Indians. In 1842 he participated in the campaigns against Vasquez and Woll. He served alongside his brother Napoleon as a member of the Snively Expedition in 1843. During the Civil War he enlisted in the Confederate Army. Benjamin married in 1852 and had seven children. He died in San Marcos in 1902.

William Brookfield

William Brookfieldby Kathy Carter

William Charles and Emma Lalliet Brookfield married in Cayuga County, New York in August of 1813. In eleven years they became parents to two daughters and four sons. He was a civil engineer and surveyor and the family lived near Detroit, Michigan before immigrating to Texas.

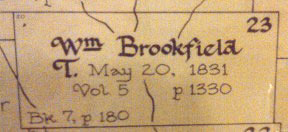

On May 20, 1831 William Brookfield received title to a league of land in Stephen F. Austin’s Second Colony. It was situated on the Navidad River, near present day Dubina. When he sold this land ten years later he reserved a small section of it as a cemetery because his wife Emma and one child, most likely their youngest son, were buried there.

In 1832, Brookfield and Musgrove Evans (also from Michigan) purchased the David Berry league of land that stretched from the high bluff across from La Grange all the way to the area of present day Hostyn. The La Bahia Road crossed the property and Brookfield built a large two story native fieldstone home on a hilltop overlooking the road. Part of the home still stands today.

In 1832, Brookfield and Musgrove Evans (also from Michigan) purchased the David Berry league of land that stretched from the high bluff across from La Grange all the way to the area of present day Hostyn. The La Bahia Road crossed the property and Brookfield built a large two story native fieldstone home on a hilltop overlooking the road. Part of the home still stands today.

During the Texas Revolution, William Brookfield supported the Texas Army and Navy with funds and supplies. On January 29, 1836 Brookfield advanced $200 to William Barrett Travis as he and his company passed through the area on their way to the Alamo. Six weeks later Brookfield provided “one elegant bay horse … to carry the express from Bexar to Washington (on-the Brazos) reporting the fall of the Alamo.” The only casualty of the Alamo from this area was Samuel B. Evans, son of Musgrove Evans. Two of Brookfield’s sons, William and Francis, joined the Texas Army and fought at the battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836.

In December 1837, the Second Congress of the Republic of Texas appointed a committee to select a permanent site for a state capital. They met at John Henry Moore’s plantation and signed tentative contracts to purchase the John Eblin league, adjacent to the town of La Grange, and the Brookfield and Evans league on the opposite side of the Colorado River. Other landowners offered to donate some of their property until “all the vacant land lying within a radius of nine miles” was reserved for the government.

After a majority vote of both houses of Congress in April 1838, the lands in Fayette County were chosen for the new capital but President Sam Houston vetoed the bill, some believing he wanted the capital to stay in the town that bore his name. A few months later a new congress and a new president chose Austin as the state capital. The citizens of Fayette County did not take these decisions lightly and on October 25, 1839, the Fayette County Grand Jury, led by foreman William Brookfield, returned the one and only public indictment against the Republic of Texas for “Inconsistent Legislative Acts.”

Trouble with Mexico continued and in September 1842, the Mexican army captured San Antonio. Texas forces were quick to respond and camped east of the city on Salado Creek. In Fayette County, Francis E. Brookfield and David Berry joined a group of men intent upon joining the Texans. Captain Nicholas Dawson was in command on the afternoon of September 18th, 1842 when his company rode into the middle of a battle and was quickly massacred by the Mexican forces. Dawson, Brookfield and Berry lay dead on the prairie alongside 33 other brave Texans. Their bodies were buried on the battlefield.

In 1848 the remains of the gallant men of the Mier Expedition and the Dawson Massacre were exhumed and brought to La Grange. A suitable burial spot on the original David Berry league was donated by William Brookfield and on September 18, 1848 the remains of the Texas heroes were placed in a single stone vault on the high bluff overlooking the Colorado River and the city.

Brookfield’s oldest child, Emma married Vincent Luray Evans, son of Musgrove Evans, and they had several children before he died “out west”. In 1848 she married German immigrant Julius Cremer and lived in the Brookfield home until her death in 1877. She is buried in the Hostyn Catholic Cemetery.

William Brookfield died in New York City in 1849 and is buried there. At the time of his death, he owned 3,128 acres on the Navidad River and 743 acres on Buckner’s Creek. Aylett C. "Strap" Buckner

Aylett C. "Strap" Bucknerby Kathy Carter

Aylett C. “Strap” Buckner, legendary frontier hero, was born about 1787 in Caroline County, Virginia.

He made his first visit to Texas in 1812. By then the ownership of Texas was contested since the United States claimed that the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 included all of Texas, while Spain believed the boundary rested at the Red River. Many men, lured by the promise of free land and potential wealth, joined various expeditions to try to gain control of Texas from Spain.

Aylett Buckner was a member of three such expeditions, the first as a member of the unsuccessful Gutierrez-Magee Expedition. He returned in 1816 with another failed expedition led by Francisco Xavier Mina. Buckner made his last journey to Texas when he was recruited to join Dr. James Long’s expedition as a citizen soldier in 1819.

Long’s effort failed in 1821 but by then Buckner had found a new home in Texas. He settled in the untamed wilderness alongside a tributary of the Colorado River across from present day La Grange. He was a member of Stephen F. Austin’s “Old Three Hundred” and was one of the first men to build a cabin along the river and the first to plow a field. This later caused escalating difficulties between the two as Austin promised the land to other settlers and Buckner would not release his hold on it. At one point, Austin ordered Buckner arrested to “answer charges of disorderly and seditious conduct” against the peace and tranquility of the Colony. Eventually their arguments were worked out and Buckner received his land.

By 1825, he was operating a trading post, dealing in livestock, farming and fighting Indians. Buckner felt that he had lost more property to the Indians than any other man in the entire colony. In 1826, Captain Aylett C. Buckner commanded a militia company against the Waco and Tawakoni tribes and later defeated a band of Karankawa who had murdered two families.

Aylett C. Buckner lost his life on June 26, 1832 during the Battle of Velasco. A company of Texans had gone to Brazoria to secure a cannon when they were drawn into a fight with Mexican forces at nearby Fort Velasco. The fight lasted two days until the Mexicans ran out of ammunition and surrendered. Buckner and six or seven other Texans, including his neighbors Leander Woods and Andrew Castleman, were the first to sacrifice their lives in the clash between the colonists and the Mexican government that would lead to revolution and independence.

Aylett C. Buckner was a man of giant stature with a freckled face and a head of heavy hair “as red as a flame”. Though he was physically large his status as a hero of folklore as Strap Buckner is even larger.

Strap possessed the strength of ten lions and like many giants he was friendly and good-natured, so much so that he went about the colony knocking men down as he greeted them with a tap on the back. If, by chance, he injured anyone, he would carry them to his home, nurse them back to health so that he might knock them down again. Strap eventually knocked down every man in Austin’s colony at least three times, including Austin himself.

Tales of his exploits grew when a black bull, known as “Noche” mysteriously appeared in the colony terrorizing the settlers. Buckner challenged the bull to a fight. With a red blanket thrown over his shoulder and no weapons, Strap strode onto the prairie where “Noche” twisted his tail, pawed the earth, and bellowed mightily. Strap pawed and roared back and when the bull charged, Strap stood his ground and met him with a resounding blow to his head. The bull staggered, turned tail and fled, never to be seen in the colony again.

Legend has Strap clearing out the Indians by knocking down all the warriors and instead of scalping him the Indians praised him and named him “Kokulblothetoff”, meaning the “Red Son of Blue Thunder”. The chief offered Strap an Indian princess for a bride but Strap declined refusing to have his powers weakened by a woman.

Strap had now knocked down all the living things in the colony. He took to drinking his jug of “demon rum” and proclaimed himself champion of the world. He defied all that lived and then three times challenged the Devil. At nightfall a violent storm began shaking Strap’s cabin and in the middle of a blinding sheet of lightning and deafening crash of thunder, the Devil appeared to answer Strap’s challenge. The next morning the battle began in a raging storm and lasted all day until the Devil bested Strap and carried him away. Three months later Strap returned bearing a sad, far-away look and retreated to his cabin for another three months. Then one night a giant blue flame arose from Strap’s cabin and out of the flame came a horse carrying a gigantic man and a cowering red Devil. The next morning the cabin was found in ashes and Strap was no more.

And now the story goes that on stormy nights, while the wind howls, and lightning flashes and thunder cracks, the ghost of Strap Buckner with red hair streaming behind, rides through the air up and down the Colorado Valley.

Jesse Burnam

Jesse Burnamby Kathy Carter

Jesse Burnam was born in Madison County, Kentucky on September 15, 1792. His father died and his mother moved the family to Shelbyville, Tennessee where Jesse married Temperance in 1812. Jesse traded for a small piece of land but when neighbors “got close enough to hear them call hogs” Jesse felt “cramped” and they had to move. Burnam contracted consumption (tuberculosis) and was advised to move to a warmer climate. The couple and their four children left Tennessee for Texas settling on the west bank of the Colorado River about twelve miles below present day La Grange in the fall of 1822.

In 1824 Jesse Burnam was granted title to a league of land (4428 acres) as one of Stephen F. Austin’s ”Old Three Hundred”. He was elected Captain of the local militia and was charged with mounting a defense against the various Indian tribes that caused constant and considerable trouble to the settlers. Captain Burnam was kept busy in this position and took part in many Indian encounters.

Burnam also took part in one of the only surgical reports on record from the early days of Austin’s Colony. A man by the name of Parker lived across the river from Burnam and one of his legs was “terribly diseased”. He begged to have the leg taken off for two months before Burnam and three other men agreed to the amputation. They undertook the job with a dull saw and shoe knife, the only tools they had. Burnam removed Parker’s suspenders and used them to create a rude tourniquet before the operation began. One man was to cut the flesh, another would cut the bone, Burnam would hold the flesh back, and the fourth man was do the sewing with a heated and bent needle. After the surgery, Parker rested easy for three days, but then complained that the heel on his other leg hurt. He died on the eleventh day.

Jesse established Burnam’s Crossing, a combination trading post and ferry, near his fortified residence on the lower La Bahia Road. It was popular stopping point and river crossing for settlers and travelers.

Temperance Burnam was the mother of nine children when she died in 1833 leaving Jesse with a house full of young children. They needed schooling so he took them 15 miles to the only school in the area established at David Breeding’s home. He built a shed tent with a long bedstead for his daughters to sleep in while his sons slept under the trees.

Jesse Burnam participated in the Convention of 1832, the first political gathering of colonists in Mexican Texas. The delegates adopted a series of resolutions requesting changes in the governance of Texas including tax relief, immigration reform and full statehood separate from Mexico.

By August of 1835 war with Mexico was imminent. In November Jesse Burnam served as a delegate to the General Consultation that created a provisional government for an independent Texas.

In late January 1836 William Barrett Travis and his company spent several days at his “Head Quarters at Burnam’s” before going on to the Alamo. A month later, Colonel Travis found himself in the San Antonio mission “besieged by a thousand or more of the Mexicans under Santa Anna”.

The battle of the Alamo lasted 13 days and ended with the death of all its defenders on March 6, 1836. About the same time General Sam Houston was “lingering” all night, all day and all night again at Burnam’s Crossing before making his way to his gathering army in Gonzales. There he learned that the Alamo had fallen and that Santa Anna and his army of more than 3000 men planned to sweep across Texas destroying everything in their path.

Houston ordered a retreat back Burnam’s Crossing. He reached the Colorado River on March 17, 1836 with about 700 men. He intended to make a stand against the Mexican army but changed his mind when he found out that the enemy was only a few miles away. He ordered another retreat and it took two days for Burnam’s ferry to get all the men, horses, baggage and fleeing settlers across the river. Heavy spring rains were causing the river to rise and swell making the crossing even more difficult, but it also kept the Mexican army at bay for a few more days. Two of Jesse Burnam’s sons joined Houston’s army and participated in the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836.

The first session of the First Congress of the Republic of Texas was held in the fall of 1836 and John G. Robison represented this area. He was killed by Indians in February 1837 and Jesse Burnam was elected as his replacement to the second session held in May and June 1837.

The Burnam children weathered the years of turmoil with their father but longed for a mother and felt that the widow of James J. Ross, Nancy Cummins Ross would “make us a good mother”. She agreed and married Jesse on July 21, 1837. They had seven children.

By 1855, the population of Fayette County was close to 4000 and Jesse felt “cramped” again and had to move. The family settled in Burnet County and Jesse died at his home on Double Horn Creek on April 30, 1883.

Sylvanus Castleman

Sylvanus Castlemanby Kathy Carter

Sylvanus Castleman and Elizabeth Lucas married in Davidson County, Tennessee in 1803 and their first five children, Nancy, Andrew, Sarah, Elizabeth and Lavinia were born there.

During the War of 1812, Sylvanus served as a Mounted Ranger in the Tennessee Militia. Shortly thereafter the family moved to Missouri where two more children, Benjamin and Jacob, were born.

While in Missouri, Sylvanus became acquainted with Moses Austin who in 1819 was developing a plan to settle an American colony of 300 families in Spanish Texas. Austin and two American companions went to San Antonio to present the colonization proposal to the Spanish governor who endorsed it on December 26, 1820.

Sylvanus Castleman may have been one of Austin’s traveling companions or he may have already been in Texas because as Moses Austin was about to return to Missouri to settle his affairs he sent a letter to his friend, Baron de Bastrop, mentioning that he had been at Mr. Castleman’s in January 1821.

Moses Austin died in Missouri on June 10, 1821 and his son Stephen F. Austin carried out his colonization plan. In March 1822, Sylvanus paid Austin for surveying his land and securing a title for it in the Province of Texas.

The rest of the Castleman family joined Sylvanus on the Colorado River prior to March 1823. The last Castleman child, son John, was born in Texas.

On July 7, 1824 Castleman officially received title to several tracts of land as a member of Austin’s “Old Three Hundred” colony but he lived on his one-half league (2214 acres) located on the west side of the Colorado River in a big bend about six miles above present day La Grange.

The Castleman homestead was a popular place for travelers and visitors passing through the area. Baron de Bastrop and Stephen F. Austin were frequent visitors and while they were in residence their letters were headlined with the notation: “From Castleman’s on the Colorado.”

The Castleman homestead was also a popular place for the Indians to harass and rob. They stole all of the horses and robbed their home taking the family quilts, bedding, clothing and table furniture. Castleman thought peace could be made with them until they assaulted his family. Sylvanus and his eldest son, Andrew were taken captive while working in the field and Andrew’s wife Nancy was frightened out of the house and fled to the river bottom carrying her three week old daughter Milly in her arms. The Indians took the tiny infant and began passing her around while Nancy begged them not to hurt her. When the savages threatened to drown the baby in the river Nancy began screaming hysterically. This shocked and impressed the Indians and they gave the baby back to her. With the help of a small boy who could speak their language Nancy was able to convince the Indians to release her husband and his father. From then on Sylvanus and his sons eagerly joined other settlers is chasing and killing the savages.

Sylvanus was a farmer and stock raiser as well as a "Politico", having been elected Alcalde (judge) of the colony on January 26, 1824.

It is believed that Sylvanus Castleman died sometime in 1831. According to some reports, he “became deranged and committed suicide” by slitting his own throat. It was also noted that he was “esteemed as one of the best of men”. At any rate, Sylvanus was dead before March 10, 1832 when it was announced by his widow that he was deceased and all moveable property would be sold at his residence. His burial place is unknown.

Andrew Castleman died alongside Aylett C. Buckner at the Battle of Velasco in June 1832. His widow, Nancy, remarried and the baby girl, who had been dangled over the river by the Indians, grew up and had a family of her own.

Nancy & Lavinia Castleman married brothers John & Arter Crownover. They were brothers to Mary Crownover Rabb. With these marriages two of the first families of the Fayette County area were linked.

Sarah Castleman married Alexander Brown and moved to Blanco County.

Jacob Castleman served in the Texas army during the San Jacinto Campaign in 1836. He married Sophronia Harrell Lyons. They are both buried in the Castleman family burial ground just east of present day Flatonia.

The fate of Benjamin Castleman is unknown.

John Castleman, the only child born in Texas, died in 1848 in Grimes County.

Elizabeth Lucas Castleman died in 1858 and is buried in the family cemetery near Flatonia.

Kesiah Crier (Cryer)

Kesiah Crier (Cryer)by Kathy Carter

Kesiah Crier (Cryer) was born January 19, 1797, the eighth child of Morgan and Barbara Morris Cryer. She was seven years old when her mother died in Georgia. Her father moved the family to Arkansas in 1815. The next year, Kesiah married William Hemphill, a prosperous merchant. The couple had five children but only two, Andrew and Charlotte, survived infancy. William Hemphill died in 1825 and Kesiah married a second time to Thomas Jacobs and they had one child, Henry Franklin Jacobs, before Thomas died in 1829.

Kesiah Jacobs and her three children made the journey to Austin’s Colony in December 1830 probably because her brother, John Crier-also a widower with two children, was already living in Texas as a member of the “Old Three Hundred”. Kesiah’s sister Rebecca was married to James Cummins and also resided in Texas. John and Rebecca and their families settled along the Colorado River near the Ross and Burnam families.

On March 14, 1831 Kesiah went to San Felipe de Austin to petition the Mexican Government for a land grand as one of Austin’s colonists. She applied using her maiden name, Kesiah Crier, and stated that she was a widow with a family of three children that wanted to locate permanently in Texas. She had selected a league of land situated on West Fork Creek, a tributary of Navidad Creek. She agreed to settle and cultivate the land according to the colonization laws. The next day, Samuel May Williams, Austin’s agent, gave his approval stating that she was a much respected widow who was entitled to her chosen land. The Mexican land commissioner ordered her land surveyed so a title could be issued.

Kesiah received the title to her league on May 10 1831, making her one of the first women in Texas to be granted such a large amount of land by the Mexican government. Four twenty-fifths of her league was suitable for farming and the rest of the 4,428 acres were pasture land. The old community of Lyons and the present day city of Schulenburg sit on the Crier league.

The southern section of present day Fayette County was still an unbroken wilderness and largely unsettled when Kesiah and her family arrived at her league. Their only neighbors were the James Lyons family. The two families were the only white settlers in the area. It is believed that Henry Franklin Jacobs died shortly after the family arrived at their new home.

Kesiah married “Yankee George” Taylor and their son John Crier Taylor was born in 1832. The family spent the next few years under near constant threat of Indian raids and Mexican invasions. Family stories relate that during the Texas Revolution, the Taylor family fled to the safety of East Texas during the Runaway Scrape and along the way Andrew Hemphill drowned in Galveston Bay. After the family returned home two more children, Nancy Ann and George Morgan Taylor were born.

Indian raids continued to be a threat and in the fall of 1837, about two miles from Kesiah’s property line, a Comanche war party attacked the James Lyons family. They killed the father and carried off his son into ten years of captivity.

In 1845, George and Kesiah started selling off pieces of the Crier league to families arriving from the United States. As the population of the south end of the county grew, roads were developed across the land. A trading post was established near the "Cotton Road" to Mexico and the town of Lyons developed. By 1860 the thriving community had several stores, a Masonic Lodge, church, school, and a post office.

George Taylor died in 1862 and Kesiah moved to Corpus Christi to live with her daughter Nancy. She died after 1870. George and Kesiah Taylor may be buried in unmarked graves in the Taylor section of the Old Navidad Baptist Cemetery.

After the Civil War the Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway extended its line toward San Antonio and passed two miles north of Lyons. In 1874 the post office, the local businesses, and the Masonic lodge moved to the railroad and formed the nucleus of the new town of Schulenburg.

In 1881, Kesiah’s youngest son, George Morgan Taylor, sold off the family’s last interest in the Crier league. The last of Kesiah’s descendants to live on the K. Crier league, a great-graddaughter, died in 1965.

John Winfield Scott Dancy

John Winfield Scott Dancyby Kathy Carter

John Winfield Scott Dancy was born September 3, 1810 in Virginia. He grew up in Alabama and attended college in Tennessee. He married in 1835 but his young wife died the following year.

On November 21, 1836 John Dancy bid farewell to his family in Decatur, Alabama and started for Texas. He traveled overland to New Orleans and then by boat to Texas, arriving at the port of Velasco on December 28, 1836.

The “Father of Texas”, General Stephen F. Austin, had died the day before and the steamboat Yellowstone was in port carrying his body to his burial place at Peach Point. Also on board were President Sam Houston, the members of his Cabinet and other government officials. John Dancy joined this group when the steamer returned upriver.

Dancy traveled all around the coastal areas and then ventured to San Antonio. In April 1837 he set out for the Colorado River. Traveling by horseback, it took five days to reach Colonel Henry Manton’s home at the La Bahia crossing. Dancy rode over the countryside visiting F. W. Grassmeyer and the Rabb family. Mr. Dancy was so taken with the view from atop the bluff (Monument Hill) that he purchased sizable acreage from Henry Manton before leaving the Colorado.

Dancy went home to Alabama but was back on the Colorado by early January 1838. Fayette County had been established the month before and the town of La Grange was declared the county seat.

In February 1838, John W. S. Dancy, Henry Manton and five other men established the town of Colorado City on the west bank of the Colorado River directly opposite John Henry Moore’s town of La Grange. Elaborate plans called for the development of 5,000 acres with 156 blocks of residential and commercial property but the town never progressed beyond the plat stage.

Dancy built his home and plantation on his Colorado City property. He grew cotton, wheat, corn and other vegetables and fruits. He installed a hydraulic watering system to provide irrigation for his crops.

John Dancy joined the armies of Texas and the United States during the 1840’s. He served as a private under Captain Nicholas Dawson and Colonel John Henry Moore in the last major expedition by Texas troops against the Comanche in 1840. In early 1842 he once again served under Captain Dawson during the Vasquez Raid. In 1847 he was a member of U.S. Army Spy Company during the Mexican War.

Dancy began a long political career in 1841, serving in the Senate of the Sixth Congress of the Republic of Texas. In 1847, Senator Dancy was elected to serve in the Texas state legislature. During the next ten years he served two terms in the Senate and one in the House of Representatives.

Transportation was a major problem facing early settlers in Texas and John Dancy firmly believed that the development of railroads would be a great economic boon to Texas. His early advocacy of railroad development earned him the nickname "Father of Texas Railroads."

On October 25, 1849 he married for the second time to Lucy Ann Nowlin of Austin. Together they had six children including one son and five daughters.

In 1850 Dancy became a newspaper man when he served as the editor of the weekly newspaper called the “Texas Monument”. Its purpose was to raise funds for a proposed monument on the bluff to honor the Dawson & Mier men but the effort failed.

In 1853 Senator Dancy decided to run for Governor of Texas. In the gubernatorial election of August 1853 there were six candidates and Dancy placed last with only 315 votes.

His last official service was as one of three Fayette County delegates to the 1861 secession convention in Austin that approved Texas’ withdrawal from the United States to join the Confederate States of America.

On February 13, 1866, at the age of 56, John Winfield Scott Dancy died and was laid to rest in the Old La Grange City Cemetery. He left behind a detailed diary of his life beginning with his journey to Texas in 1836.

Nicholas Mosby Dawson

Nicholas Mosby Dawsonby Kathy Carter

Nicholas Mosby Dawson was born in Kentucky to George and Frances Mosby Dawson. He was raised in Sparta, White County, Tennessee. He followed his friend John Henry Moore and his cousins William and Nicholas Eastland to Texas.

John Henry Moore, William Mosby Eastland, and Nicholas Mosby Dawson were destined to play courageous and spectacular roles in the history of Texas.

It is believed that Nicholas Dawson was in New Orleans when he was recruited to fight in the Texas Revolution. He arrived by ship at the port of Velasco and on January 29, 1836, he enlisted in the Texas Army for two years as a “permanent volunteer”. He was elected as second lieutenant and two months later his company joined the main force of Sam Houston’s army on their retreat from the Colorado River.

At the battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, Second Lieutenant Nicholas Mosby Dawson of Company “B”, served under the command of Colonel Edward Burleson in the First Regiment, Texas Volunteers.

Dawson served in the Texas Army until May 1837 and then settled in this area to be near his family. He continued his military pursuits by serving in several campaigns against Indian tribes.

Despite the decisive victory at San Jacinto, Texas continued to be harassed by Mexican invasions. In March 1842, General Raphael Vasquez raided and briefly captured San Antonio before retreating. Texas forces pursued them to the border, one company being under the command of Captain Nicholas Mosby Dawson.

A few months later, General Adrian Woll invaded Texas again, attacking and capturing San Antonio on September 11, 1842, taking many prominent citizens as prisoners.

The news reached La Grange on September 14th and a spirited meeting was held where the citizens of the county called for immediate and prompt action. On September 15th, Nicholas Mosby Dawson and other volunteers willing to ride to the defense of San Antonio left home at once, starting as they got ready, four or five at a time, or a dozen together, riding night and day, until they reached Nash’s Creek, sixty miles from La Grange and fifty miles from San Antonio. By this time 53 men were in the group and Dawson was elected Captain.

Colonel Matthew Caldwell and his army were encamped on Salado Creek east of San Antonio and proceeded to draw Woll’s army out of the city to engage them in battle. Late on September 17th, Caldwell sent out an express rider with a message that "urged on all companies" to join him. Dawson and his men hurriedly broke camp, saddled their tired horses and rode all night. At daylight on the morning of September 18th they finally stopped long enough to make coffee, the first time they had the opportunity to do so since leaving home.

A scout was sent ahead to determine Caldwell's position and he soon found the battle already underway. Dawson and his men advanced, urging their exhausted horses into a weary gallop until they could see the battlefield about two miles in the distance. They did not know that they were approaching the rear of the Mexican army until it was too late. Woll knew his forces would be in grave danger if the Texans attacked from the front and rear so he sent 400 men and one piece of artillery to crush the newly discovered Texans. At around 3 or 4 p.m., Dawson and his men realized that the approaching troops were Mexican and "was too great to contend with successfully, but retreat was out of the question”. Many of the horses were broken down and one or two men were on foot.

Dawson moved his men to a sparse mesquite thicket covering about two acres in the midst of a prairie (near present day Fort Sam Houston) and ordered his men to dismount and tie their horses. They prepared to stand and fight.

They were quickly surrounded but were able to keep the enemy at bay with their rifles; however, once the Mexican cannon began to open fire, Dawson's force began to be slaughtered. Wounded, Dawson raised a white flag trying to surrender but in confusion both sides continued to fire and Dawson was killed. His "last and dying words" were "sell your lives as dearly as possible--let victory be purchased with blood." About sundown, the Mexicans made their final assault and the battle became one of hand to hand combat. After little more than one hour, the battle ended with 36 Texans killed, 15 taken prisoner and two escaped.

The bodies of Dawson and his men were stripped of their clothing and searched for valuables, mutilated and left where they had fallen. During the night a cold rain fell and cleansed the bodies of blood giving them a marble-like appearance. At sunrise Caldwell's men located and inspected Dawson's battleground and the men were buried on the site in shallow graves.

In 1848 the remains of the gallant Texans who died in the "Dawson Massacre" were exhumed and brought to La Grange. On September 18, 1848 they, with the remains of the men who were executed in the “Mier Expedition” were placed in a single stone vault on a hill overlooking the Colorado River and the city.

William Mosby Eastland

William Mosby Eastlandby Kathy Carter

William Mosby Eastland was born in Kentucky to Thomas Butler and Nancy Mosby Eastland. The Eastland, Dawson and Moore families were related and it is believed that after John Henry Moore migrated to Texas he wrote to his family and friends describing the great opportunities and possibilities to be found in Texas. William Mosby Eastland was the first to follow Moore to Texas. In 1833 he settled in the area, built a saw mill, and engaged in the lumber business. His brother Nicholas Washington Eastland, his nephew Robert Moore Eastland and his cousin Nicholas Mosby Dawson along with other family members soon followed William to Texas.

John Henry Moore, William Mosby Eastland, and Nicholas Mosby Dawson, were destined to play courageous and spectacular roles in the history of Texas.

Eastland began his military service in July 1835 when he was appointed first lieutenant of a volunteer company under Colonel John Henry Moore in a three month campaign against the Waco and Tawakoni Indians. On his return, he joined the volunteer army of Texas and participated in the “Storming and Capture of Bexar” in December 1835.

In March 1836 Eastland re-enlisted in the army and at the battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, First Lieutenant William Mosby Eastland of Company “F”, served under the command of Colonel Edward Burleson in the First Regiment, Texas Volunteers. After the eighteen minute battle General Sam Houston ordered his men to stop killing the Mexican soldiers and begin taking them prisoner. Eastland’s reported response: "Boys, you know how to take prisoners, take them with the butt of guns, remember the Alamo, remember La Bahia (Goliad), and club guns, right & left, and knock their brains out."

Eastland enlisted in the Texas Rangers in September 1836 and by December he was a commander, but his attempt to instill military discipline into his ranks failed and the men "marched out, stacked their arms, told him to go to hell and they would go home." However, Eastland yielded gracefully, maintained the rangers' respect, and continued to serve until late January 1838.

In 1839, he was back to chasing Indians alongside John Henry Moore. He was elected captain of one of three companies that fought the Comanche on the upper Colorado River.

Trouble with Mexico continued and in September 1842, the Mexican army marched into San Antonio and captured the city. Captain Matthew Caldwell and his forces were the first to respond and they set up camp east of the city on Salado Creek. In Fayette County, Nicholas Mosby Dawson and Robert Moore Eastland joined a group of men intent upon joining Caldwell. Dawson was in command on the afternoon of September 18th, 1842 when his company rode into the middle of the battle and was quickly massacred by the Mexican forces. Dawson and Robert Moore Eastland lay dead on the prairie alongside 34 other brave Texans.

William Mosby Eastland arrived too late to take part in the battle of Salado Creek but he participated in the pursuit of the retreating Mexican army. The Texas Army reached the Rio Grande River without engaging the Mexican forces and they were ordered to disband and return home. Many of the Texans disagreed and about three hundred men disobeyed and continued their march into Mexico. William Mosby Eastland, eager to avenge the deaths of his cousin and nephew, favored the invasion and joined the "Mier Expedition" where he was elected company captain. A fierce battle was fought at Mier, Mexico on Christmas night, 1842, in which the Texans, though greatly outnumbered, were victorious. The Mexicans were reinforced on the following day and the Texans had no choice except to surrender. The men were started on a forced march to a prison deep in Mexico. On February 10, 1843,they reached a Mexican ranch called Hacienda Salado. Early the next morning the men "without arms or knives--not even a penknife--were able to embark upon a daring undertaking" when they overpowered their guards and escaped to the mountains. One hundred seventy six men were eventually recaptured and returned to Hacienda Salado where orders were received from Santa Anna to execute every tenth man. Black and white beans, seventeen of which were black, were placed in an earthen jar from which each Texan was forced to draw. Captain William Mosby Eastland was the only officer to draw a black bean. On March 25, 1843, the seventeen unfortunates were led into a courtyard, blindfolded, and shot to death. Their bodies were thrown into a single trench and buried.

In 1848 the remains of the gallant Texans were exhumed and brought to LaGrange, the home of Captain William Mosby Eastland. On September 18, 1848 they, with the remains of the men who fell in the "Dawson Massacre", were placed in a single stone vault on a hill overlooking the Colorado River and the city.

Nathaniel Wright Faison

Nathaniel Wright Faisonby Kathy Carter

Nathaniel Wright Faison was born April 24, 1817 in North Carolina to Wright and Mary Faison. As a teenager, he moved with his family to Western Tennessee where he became a land agent and surveyor. He carried his profession with him to Texas in 1839 and within a year he paid taxes to Fayette County on one town lot, one silver watch, and one saddle horse.

In 1840 Faison served as a captain under Colonel John Henry Moore in the last major expedition by Texas troops against the Comanche.

Despite the decisive victory at San Jacinto, Texas continued to be harassed by Mexico. On September 11, 1842, General Adrian Woll invaded Texas, attacking and capturing San Antonio.

The news reached La Grange on September 14th and the next day Nicholas Dawson, Nathaniel Faison, and other volunteers willing to ride to the defense of San Antonio left home riding night and day until they reached Nash’s Creek, sixty miles from La Grange.

Colonel Matthew Caldwell and his army were encamped on Salado Creek east of San Antonio and proceeded to draw Woll’s army out of the city to engage them in battle. Late on September 17th, Caldwell sent out an express rider with a message that "urged on all companies" to join him. Captain Dawson and his men hurriedly broke camp, saddled their tired horses and rode all night.

On the morning of September 18th Dawson’s company determined Caldwell's position and found the battle already underway. They advanced until they could see the battlefield about two miles in the distance. They did not know that they were approaching the rear of the Mexican army until it was too late. Woll sent 400 men and one piece of artillery to crush the newly discovered Texans. By the time Dawson and his men realized that the approaching troops were Mexican "retreat was out of the question”.

The men sought cover in a sparse mesquite thicket and prepared to stand and fight.

They were quickly surrounded but were able to keep the enemy at bay with their rifles; however, once the Mexican cannon began to open fire, Dawson's force began to be slaughtered. About sundown, the Mexicans made their final assault and the battle became one of hand to hand combat.

When the battle ended, fifteen men, including Nathaniel Wright Faison, had survived the carnage. They were disarmed and stripped of everything except their shirts and pants. Their hands were tied behind their backs and their pockets turned inside out in search of money. Only Faison had any and that was about two dollars but he wore a ring that one of the Mexicans wanted. "Faison thought he could not get it off but when the Mexican drew his knife and made signs that he would take off the finger, Faison made another try at the ring and found it came off easily".

Two days later, Faison and the other prisoners were marched on foot out of San Antonio along with the Mexican army bound for Mexico. Three months and a thousand miles later, the men reached their destination, Perote Prison, below Mexico City. The men were chained together and made to work. Their rations were poor and they suffered severe illnesses and several men died. Nathaniel Faison and the rest of the surviving men of the Dawson Company were released on March 24, 1844. They had been in prison for nineteen months.

Faison returned to La Grange and in 1845 he was elected County Clerk and held the office until 1854.

In 1866 Faison bought a house on Jefferson Street that now bears his name.

Faison worked as a land agent and amassed a fortune in real estate and gold. Just prior to his death he owned 35,000 acres of land in 14 different counties and nearly $5,000 in gold and silver. He died at age 52 on June 29, 1870 and is buried in the Old La Grange City Cemetery.

Frederick William Grasmeyer

Frederick William Grasmeyerby Kathy Carter

Frederick William Grasmeyer was born on Christmas Day 1800 in Hamburg Germany. He was one of the first German citizens to immigrate to Texas and the first to acquire land in present day Fayette County. On August 4, 1831 he received title to a quarter league of land (1107 acres) in Stephen F. Austin’s Little Colony. Grasmeyer’s land was along the Colorado River about midway between the La Bahia Road and the town of Mina (Bastrop). He established a trading post, cotton gin and mill on his homestead and built a river landing for his ferry boat.

Grasmeyer’s Ferry was used to help the colonists escape the Mexican army and the Comanche Indians during the Texas Revolution. One of Grasmeyer’s neighbors related that after the fall of the Alamo the settlers knew there was nothing for them to do but run. The families gathered together and were camped in a field when Comanche warriors stampeded and stole their horses and then came back and surrounded the group. The men with their guns and the women with sticks went out to make a stand. After a while the Indians rode off towards Grasmeyer’s gin. He had hidden a lot of his goods under the cotton and expected it all to be burned but the Indians only cut the gin bands.

On December 14, 1837, the Congress of the Republic of Texas took two actions that were of vital importance to F. W. Grasmeyer. President Sam Houston signed the bill creating Fayette County and the Colorado Navigation Company was incorporated.

The county was carved out of the Mexican municipalities of Mina and Colorado. Grasmeyer's Ferry was chosen as the western boundary line between Mina (Bastrop) and Fayette County. One of the first acts the new county government undertook was to define a network of “highways” in the county and the road from La Grange to Bastrop by Grasmeyer’s Ferry was the first listed. However, overland travel in early Texas was often difficult and dangerous and Grasmeyer envisioned great economic benefits for himself and Austin’s entire colony if the Colorado River could be used to easily transport goods and people from the coast to Austin and back. The most serious drawback to navigation of the Colorado was "the raft”, a miles long mass of timber and debris choking off the river before it reached the Gulf of Mexico. For nearly two decades Grasmeyer and the Colorado Navigation Company attempted to keep the river open to the Gulf with little success. The outbreak of the Civil War and the coming of the railroads brought about the end of navigation on the Colorado.

In the early 1850s Grasmeyer moved to La Grange and was involved in several businesses, investment ventures, and many real estate deals. He also owned interests in silver mines in New Mexico.

The first three months of 1861 brought turmoil to Fayette County as the citizens struggled with the secession movement prior to the Civil War. On March 21, 1861 a scathing editorial against the character of Frederick Grasmeyer was printed in the local newspaper. The writer alleged that “Grass” was a traitor to Texas going all the way back to the Texas Revolution and then pronounced him as an abolitionist in hiding and accused him of secretly plotting to free slaves. One witness stated that during the Revolution of 1836 Sam Houston ordered that Grasmeyer be brought in for questioning but “Grass” could not be found because he was hiding with the Mexican Army. Weeks later Grasmeyer distributed his rebuttal in a lengthy broadside entitled “F.W. Grasmeyer’s Vindication”. He disputed each and every charge against him and included a letter from Sam Houston stating that Houston found “not a single fact” that implicated Grasmeyer “in the slightest degree” and Houston hoped that Grasmeyer would “not be annoyed further in relation to these base reports”. Many of the accusers in the original article also confessed that the allegations were either incorrect or that they never said them. Citizens from Fayette and Colorado counties both signed proclamations declaring Frederick William Grasmeyer innocent of treason.

Grasmeyer returned to his family in Germany several times over the years, the last being in 1885 when he was nearly 85 years old. Two years later he was diagnosed with breast cancer and traveled to San Antonio for surgical treatment. The surgeons removed two large tumors but Grasmeyer was too aged and frail to survive. He died on May 2, 1887 and his body was brought back to La Grange by train. He was laid to rest in the Old La Grange City Cemetery.

At the time of his death Grasmeyer had numerous land holdings throughout central Texas and his substantial estate was divided among quite a few people in the States and abroad. He left a sizeable donation and his extensive personal library to start a library association in La Grange The remainder of his estate went to his niece and her husband who moved to Fayette County from Russia.

Asa Hill Family

Asa Hill Familyby Kathy Carter

Asa Hill was born around 1788 in Hillsboro, North Carolina (near Fayetteville & La Grange, NC) to Isaac and Lucy Wallace Hill. The family moved to Georgia and founded the town of Hillsboro, Georgia (near Fayetteville & La Grange, GA).

On October 6, 1808, Asa married Elizabeth Barksdale. They had thirteen children, eleven who reached maturity. The family was living in Columbus, Georgia when they immigrated to Texas in the spring of 1835.

The family was busy improving their land and building a home when news came that Santa Anna had invaded Texas and the Alamo had fallen.

Asa and his son, James Monroe Hill, set out to join the Texas Army and found them near Columbus. General Sam Houston sent Asa back home to warn all the families in the colony to flee their homes in advance of the Mexican army. The Hill family joined the “Runaway Scrape” and headed east crossing flooded creeks and rivers as they struggled along. James joined the army and at the battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, Private James Monroe Hill of Company “H”, served under the command of Colonel Edward Burleson in the First Regiment, Texas Volunteers.

The Hill family moved to Rutersville (near Fayetteville & La Grange, TX) in 1839. Rutersville College was chartered in February 1840 and eight of the Hill children were enrolled in the first class of the school.

Despite the decisive victory at San Jacinto, Texas continued to be harassed by Mexico. On September 11, 1842, General Adrian Woll invaded Texas, attacking and capturing San Antonio.

Couriers were sent out from Seguin asking for volunteers to join the Texas army. Asa and two of his sons, Jeffrey Barksdale Hill and thirteen year old John Christopher Columbus Hill answered the call. They arrived too late to take part in the battle of Salado Creek where Captain Nicholas Dawson and his company were massacred but they participated in the pursuit of the retreating Mexican army. The Texas Army reached the Rio Grande River without engaging the Mexican forces and they were ordered to disband and return home. Many of the Texans disagreed and about three hundred men, including the Hill’s, disobeyed and continued their march into Mexico in what is known as the Mier Expedition. Asa, Jeffrey and John were assigned to the company of Captain William Mosby Eastland. A fierce battle was fought at Mier, Mexico on Christmas night, 1842, in which the Texans, though greatly outnumbered, were victorious. The Mexicans were reinforced on the following day and the Texans had no choice except to surrender. Jeffrey had been wounded but Asa and John were unhurt.

Asa and Jeffrey Hill and the other captives were started on a forced march to prison deep in Mexico.

John Christopher Columbus Hill displayed such bravery and audacity during the battle at Mier that Mexican General Pedro Ampudia befriended him and sent him to President Antonio López de Santa Anna in Mexico City. Characterized as "a very shrewd and handsome boy" he was shown great favor by the president who eventually adopted him in exchange for the early release of his elderly father and wounded brother who were still prisoners of war.

Asa & Jeffrey Hill were back at home in Rutersville by the fall of 1843, more than a year ahead of the rest of the Mier captives who were not released until September 1844.

Asa Hill died on July 15, 1844 and was buried near his home. In 1975 his remains were moved to the Old La Grange City before his home site and original burial site were flooded by the Fayette Power Plant cooling pond. Elizabeth re-married in 1850 and died in Gonzales County in 1883.

Jeffrey Barksdale Hill lived in Fayette County until 1860. He served in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. He died May 6, 1901 and is buried in Gonzales County.

James Monroe Hill lived in Fayette County for more than forty years. He was a member of the Texas Veterans Association and was on the committee that recommended that the state acquire the San Jacinto battleground as a memorial which was done in 1897. He died February 14, 1904 and is buried in Austin, Tesxas.

John Christopher Columbus Hill was educated in Mexico becoming a mining and civil engineer. He kept in close touch with his Texas relatives but his home was in Mexico where he married and had children. He died in Monterrey, Nuevo León on February 16, 1904, and is buried there.

James S. Lester

James S. Lesterby Kathy Carter

James S. (Smith or Seaton) Lester was born in Virginia in 1799. He was well educated, studied law, and became a Virginia lawyer in 1831. He came to Texas in 1834 and received a land grant of one-half league (about 2,214 acres) in what would become Fayette County.

Soon after his arrival, he served with the area's famed Indian fighter, Colonel John Henry Moore, in expeditions against raiding Indian tribes.

Lester served as a delegate to the General Consultation of 1835 and was on the committee that created a provisional government for Texas independent from Mexico. In early 1836, he served in Mina (Bastrop) as a recruiter for the Texas army, seeking volunteers to send to San Antonio de Bexar to join the men who would attempt to defend the Alamo against the advancing army of Mexican dictator General Lopez de Santa Anna. A colorful band of 13 heavily armed marksmen from Tennessee rode into Mina, led by a buckskin-clad former United States Congressman named David Crockett. Knowing that the Army desperately needed all the sharpshooters it could find, Lester sent them on their way to the Alamo.

After the tragedy at the Alamo, Lester vowed that he would be with the Texas Army until Santa Anna was defeated. He was on the battlefield at San Jacinto on april 21, 1836 (his 37th birthday) where Texas won her independence and the Republic was born.

James S. Lester began his long political career in the fall of 1836 when he was elected as a Senator to the First congress of the Republic of Texas representing the District of Mina and Gonzales. He went on to serve as a Senator in the Second, Fourth and Fifth congress and as the Fayette County Representative during the third Congress. While serving in the Second Congress, on December 14, 1837, he joined with Andrew Rabb and John Henry Moore in sponsoring the petition for the creation of Fayette County. He also sponsored a bill to locate the capital of Texas in Fayette County. The bill passed in both the House and Senate but was vetoed by President Sam Houston.

Lester settled in La Grange, established and surveyed as the county seat of newly created Fayette county. Whe town lots were offered for sale, lester bought quite a few until he owned nearly 3/4 of the entire town. He was one of the original five "Town Proprietors". He partnered with William Mosby Eastland in several ventures and "Lester and Eastland" became on of the area's leading businesses. In November 1838, the partners provided the county with its most vital asset. The first county courthouse was a former grocery store purchased for $250 from Lester and Eastland and moved to the public square.

After his tenure in the legislature, Lester turned to local politics and served four years as the Chief Justice of Fayette County. Faith and education were also important to Lester and he served as a founding trustee to both Rutersville College (Methodist) and Baylor University (Baptist) during the 1840s. He served on the Baylor Board of Trustees for 21 years.

James Lester owned property on the outskirts of La Grange where a cemetery was established in 1840. In 1853, Lester officially gave the land where the Old City Cemetery is located to the citizens of La Grange to use as a burying ground.

Lester's last official service was as one of three Fayette County delegates to the 1861 secession convention in Austin that approvd Texas' withdrawal from the United States and join the Confederate States of America.

James S. Lester died a bachelor, in December 1879 and is buried in the Old La Grange City Cemetery. On his tombstone it reads "Citizen of Texas for 45 years". His grave is also marked with a red granite monument erected by the State of Texas in 1962.

James and Warren Lyons

James and Warren Lyonsby Kathy Carter

James Lyons, his wife, Martha and their children immigrated to Texas before 1830 and settled along the Navidad River in the area of present day Schulenburg.

The family lived on a five hundred acre tract in the E. Anderson league and their closest neighbor was Keziah Cryer who owned the adjacent league of land. James Lyons and his oldest sons built the family’s dwelling, a double pen “dogtrot” log cabin. James planted crops and raised cattle as most of the early settlers did.

In 1837, the southern section of present day Fayette County was still an unbroken wilderness and largely unsettled and thus unprotected from Indian attack. In the early daylight hours of a fall morning James Lyons and his youngest son, 12 year old, Warren were tending cattle in a corral near their house when a war party of Comanche Indians suddenly appeared.

James was killed instantly and Warren tried to run back to the house but was caught by the Indians. They tied him down while they went about the business of stealing the family horses and shooting into the house where Martha and the rest of the children had been scared out of their beds. When the Indians were ready to leave, they picked Warren up, threw him onto the back of a horse, tied him down and rode away with him as their captive. He spent many days tied to the horse receiving little food or water until the journey ended in a canyon many miles westward from his home

James Lyons was buried next to a daughter and son who had died soon after settling in Texas. Many years later the little family graveyard became the location of the Schulenburg City Cemetery after Martha deeded the land for that specific purpose.

A settlement was established in the area of the family homestead and named alternately, Lyonsville, Lyons Station or Lyons in their honor. The town prospered and had several stores, a Masonic Lodge, school, and a post office. It was laid out near the "Cotton Road" to Mexico.

Ten years went by and beyond vague, unreliable reports nothing was heard of Warren. All of his family, except his mother, believed him to be dead.

Warren Lyons remained with the Indians and grew up always believing the rest of his family had been killed on that fateful morning in 1837. He was taught the ways of Indian life and warfare. He became an excellent marksman with both the rifle and bow and arrow. He learned the native language and learned to love the wild, free life of the savage.

In 1847 the Indians, including 22 year old Warren Lyons, came into the settlements on a trading expedition. Two of his Fayette County neighbors were there and recognized the young man who according to skin and hair color was obviously not a native of the tribe. They spoke to him; confirming his identity and then asked Warren if he wanted to return home to his family. He was surprised to learn that his mother and siblings had survived, but he wished to remain with the Indians as he had two wives and did not want to leave them. After much discussion, and a little clever bribery, Warren agreed to visit his mother and accompanied the gentlemen home, wearing the “full garb of a wild Indian.” Once home, Warren had a hard time giving up his “eccentric” Indian ways; he would not wear the clothes given to him or sleep in the house and he refused to ride his horse with either saddle or bridle.

On July 28, 1848, Warren married Lucy Boatright and they became parents of numerous children. They lived in Lyons and Warren became quite a prosperous businessman and farmer.

Warren never gave up his “eccentric” ways and in 1850, he wrote a letter to the Governor of Texas offering his services to any spy or ranging companies in “the mountains or somewhere on the frontier”. He reminded the governor that he was “well acquainted in that part of Texas” and if given orders he could “be ready at a moment’s notice.” He got his chance a year later when he served as a Texas Ranger under General Edward Burleson.

After living in Fayette County for many years, Martha Lyons moved to Karnes County and Warren and Lucy Lyons moved to Johnson County.

The town of Lyons died in the 1870s when the Southern Pacific Railroad was built just a few miles north and the city of Schulenburg was founded.

Edward Manton

Edward Mantonby Kathy Carter

Edward Manton was born September 20, 1820 in Rhode Island to Henry and Ann Manton. His mother died when he was five and his father remarried.

In the early 1830’s, the Manton family came to Texas and settled on the west side of the Colorado River at the La Bahia crossing. Henry Manton helped develop the site of Colorado City with John W. Dancy.

In the summer of 1836, Indian attacks and cattle thefts were troubling the settlers along the Colorado River. In July 1836, at the age of fifteen, Edward Manton joined the Texas Army and served in Colonel Edward Burleson’s ranging corps of mounted rifleman.

Edward’s father died in 1840 and his step-mother, brother and sister died in 1841 leaving him to manage a large plantation and estate of nearly 3000 acres.

Despite the decisive victory at San Jacinto, Texas continued to be harassed by Mexico. On September 11, 1842, General Adrian Woll invaded Texas, attacking and capturing San Antonio.

The news reached La Grange on September 14th and the next day Nicholas Dawson, Edward Manton, and other volunteers willing to ride to the defense of San Antonio left home riding night and day until they reached Nash’s Creek, sixty miles from La Grange.

Colonel Matthew Caldwell and his army were encamped on Salado Creek east of San Antonio and proceeded to draw Woll’s army out of the city to engage them in battle. Late on September 17th, Caldwell sent out an express rider with a message that "urged on all companies" to join him. Captain Dawson and his men hurriedly broke camp, saddled their tired horses and rode all night.

On the morning of September 18th Dawson’s company determined Caldwell's position and found the battle already underway. They advanced until they could see the battlefield about two miles in the distance. They did not know that they were approaching the rear of the Mexican army until it was too late. Woll sent 400 men and one piece of artillery to crush the newly discovered Texans. By the time Dawson and his men realized that the approaching troops were Mexican "retreat was out of the question”.

The men sought cover in a sparse mesquite thicket and prepared to stand and fight.

They were quickly surrounded but were able to keep the enemy at bay with their rifles; however, once the Mexican cannon began to open fire, Dawson's force began to be slaughtered. About sundown, the Mexicans made their final assault and the battle became one of hand to hand combat.

When the battle ended, fifteen men, including Edward Manton, had survived the carnage. They were disarmed and stripped of everything except their shirts and pants. Their hands were tied behind their backs and their pockets turned inside out in search of money.

Two days later, on Edward’s twenty-second birthday, he and the other prisoners were marched on foot out of San Antonio along with the Mexican army bound for Mexico. Three months and a thousand miles later, the men reached their destination, Perote Prison, below Mexico City. The men were chained together and made to work. Their rations were poor and they suffered severe illnesses and several men died. Edward Manton and five other surviving men of the Dawson Company were released on March 24, 1844. They had been in prison for nineteen months.

Manton returned to his plantation near La Grange and over the years acquired extensive land holdings and was a prosperous farmer and rancher, owning a herd of thoroughbred Holstein cattle. In 1845 he married Sarah Rabb and they had at least nine children. After her death he married Mary Scott and had three more children. He died at his home on August 20, 1893 and is buried in the Manton family cemetery.

John Henry Moore

John Henry Mooreby Kathy Carter

John Henry Moore was born in Tennessee in 1800 to Armistead and Tabitha Bowen Moore. He attended school in Lebanon, Tennessee and then attended Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky.

The when and why of John Henry’s first visit to Texas is unknown. One tradition states that he came at the age of 18 because he found the study of Latin and Greek to be distasteful. Another source states that he was with Dr. James Long’s first expedition into Texas in 1819.

By 1821 Moore was here to stay and was one of Stephen F. Austin’s “Old Three Hundred” settlers. Almost immediately he started gaining the experience that would make him one of the most famed Indian fighters in all of Texas. In 1822, Karankawa Indians ambushed a settler precipitating the first retaliatory action against the Indians by the Anglo colonists. John Henry Moore and two others served as scouts, eventually locating the Indian camp in a canebrake near a creek. The settlers killed almost all of the Indians and Moore related "we all felt it was an act of justice and self preservation. We were too weak to furnish food for (them), and we had to be let alone to get bread for ourselves”.

On June 14th 1827, John Henry Moore married Eliza Cummins, the eighteen year-old daughter of Judge James Cummins. On their wedding day, Eliza wore a dress of “fine white muslin trimmed with ruffles and frills of the same”. Eliza was regarded as a “self-reliant woman of great refinement of mind and feelings, and above petty passions”.

On May 17, 1831, Moore received title to a half-league of land on the east bank of the Colorado River near the La Bahia Road. The road was originally an east-west Indian trail and later was used extensively by explorers, soldiers, traders, and settlers in their movements across Texas.

Moore built a two story log blockhouse to defend and house his family. It featured an elevated interior platform that a man could walk around on so he could see and shoot out of gun slits made in the walls of the second story.

By the summer of 1834 Indian depredations were so frequent that the settlers of the upper Colorado River issued a call to arms. John Henry Moore led several extended expeditions against the Indians trailing them as far as North Texas.

Colonel James J. Ross, Moore’s brother-in-law, kept company with a group of Tonkawa Indians who stole horses from other Indian tribes and the Anglo settlers. Ross refused to disassociate with the Indians so his neighbors decided to drive them out by force. In an armed confrontation, Ross was killed when Moore and two other settlers shot him.

By early 1835, Texans had realized war with Mexico would be necessary to secure their freedom. Mexico had given the settlers at Gonzales a small cannon a few years before to defend themselves against Indian attack. Mexican troops arrived demanding the return of the cannon and the townspeople refused. A call for volunteer soldiers went out and was quickly answered. The “Come and Take It” flag flew above the cannon and Colonel John Henry Moore was in command of the troops at Gonzales on October 2, 1835 when the first shot of the Texas Revolution rang out. Moore tried to negotiate with the Mexican commander but when he refused Moore “wheeled his horse and rode rapidly toward his lines, shouting, ‘Charge ‘em, boys, and give ‘em hell’”. After a short volley, the Mexican troops withdrew and the rag tag Texas army sent them back to San Antonio without the cannon and war was declared. The fighting didn’t stop until the Texans were victorious at the Battle of San Jacinto six months later.

In 1837 J. H. Moore, J. S. Lester, W. M. Eastland and two other men formed a partnership in order to create a town on Moore’s land grant at the La Bahia crossing. Moore ran advertisements in newspapers describing the advantages of the new town of La Grange and began selling lots a few months later.

On December 14, 1837, the Republic of Texas Congress passed an act to establish the county of Fayette and designated the new town of La Grange as the county seat.

Two years later, La Grange had a population of nearly 100 people living in 20 houses, mostly log cabins. There were 5 small businesses including a hotel, bar and cake shop and a grocery store. John Henry’s town may have become too crowded for him because he purchased a quarter league of land (1107 acres) about nine miles northeast of La Grange. He built a new home for his family and started raising cotton.

Indian depredations continued to plague the Republic and Moore was called upon many times to lead various campaigns against the marauders. On January 25, 1839, three companies of volunteers organized under Moore’s command with instructions “to proceed against the Comanche and other hostile Indians on our northern frontier”. W. M. Eastland and Nicholas M. Dawson were elected Captain and Lieutenant of the La Grange company. A week into the trip the men rode into a heavy sleet and snow storm, forcing them to stop and seek shelter. They were not prepared for bad weather and some of their horses froze to death. In mid February a large Comanche village was found on the San Saba River. Moore’s troops were vastly outnumbered and though hesitant, Moore and his men were determined to mount an attack. They tied their horses about a mile from the village and marched through the night to within 300 yards of camp and waited for sunrise. A fierce battle ensued but the Indians clearly had the advantage and Moore called for a retreat. The men went back for their horses only to find that all of them had been stolen. Colonel Moore reached La Grange on February 25, after traveling about 150 miles with many of his men on foot. Moore admitted years later that: "It was the tightest place I ever got into, we expected nothing else but to be sacrificed, so there was nothing to do but to put the best face upon it. So we told the Comanche to come on..."

By 1840 almost every settlement along the Colorado had been raided by the Comanche. The President of the Republic of Texas appointed Colonel John Henry Moore as “commandant of the Colorado volunteers, destined for the invasion of the haunts of our Indian enemies”. By September about 90 men had volunteered and two companies were organized in La Grange serving under Captains Dawson and Thomas J. Rabb. A third company of Lipan Apaches served as scouts. The men traveled northwest up the Colorado River valley and through the mountains for nearly 300 miles. They rode into another fierce winter storm, this time losing one man to exposure. The scouts found a Comanche camp along the Red Fork of the Colorado River with about 125 Indians in the village. At daylight on October 24, the Comanche were taken completely by surprise when Moore “sounded the yell that was caught up and vibrated throughout the command like demons.” One or two braves escaped but otherwise the Texans killed or captured the entire village. Only two Texans were wounded and none were killed.

Colonel Moore’s successful Red Fork Campaign deep into Comanche territory served to deter the Indians from further depredations on the Colorado settlements.

Despite the decisive victory at San Jacinto, Texas continued to be harassed by Mexican invasions. In March 1842, San Antonio was raided and briefly captured before Texas forces, including two companies commanded by Colonel John Henry Moore and captained by Dawson and Rabb, pursued them to the Mexican border. In September, San Antonio was captured again and a company of Fayette County men led by Captain Dawson answered Colonel Matthew Caldwell’s call for help. On September 18th, 1842, Dawson and 36 of his men were massacred in a battle with the Mexican army.

John Henry Moore joined Caldwell’s forces in pursuing the Mexican Army to the Rio Grande River. Colonel Moore and Colonel Caldwell disagreed on who should command the army and their argument delayed the Texans long enough to allow the Mexicans to escape.

By 1843 peace treaties with most of the Indian tribes in Texas had been successful. With the lessening of the Indian menace, the old Indian fighter slipped away from the public eye and settled down to a life of cotton farming and ranching.

Moore was too old to serve during the During the Civil War, but in January 1862 he made an arduous trip to Kentucky to deliver winter clothing and supplies to the troops. Three of his sons and a son-in-law served the Confederacy.

After nearly fifty years of marriage and eight children, Eliza Cummins Moore passed away in February of 1877. J. H. Moore was strong, capable, opinionated, stubborn and strict but always devoted to Eliza. It was said that only Eliza “was ever able to influence his actions and opinions”.

Toward the end of his life, Moore had some disagreements with his oldest daughter Tabitha and her husband Ira G. Killough. On October 2nd, 1878, Ira Killough was gunned down at point blank range in the presence of his wife and son. The unproven theory is that John Henry Moore convinced two of his sons and a son-in-law to ambush and kill Killough. The men were arrested, tried and acquitted of the murder. Tabitha was left to raise eight children on her own and her father clearly stated in his will that neither she nor any of her children should receive any inheritance from him.

John Henry Moore died at the age of 80 on December 2nd, 1880 and was buried next to Eliza in the family cemetery eight miles north of La Grange. The local newspaper carried a lengthy obituary extolling his many accomplishments and virtues. One week later a rebuttal was printed refuting those claims.

William Rabb

William Rabbby Kathy Carter

William Rabb was born in 1770 in Fayette County, German Township, Pennsylvania. His father owned and operated a grist and saw mill, a whiskey distillery and a mercantile business. In time, the Rabb’s became one of the wealthiest and most influential families in the area.

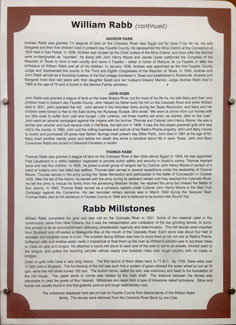

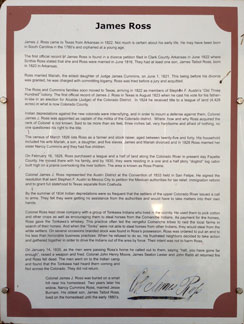

William and Mary Smalley married around 1789 and the couple had five children, Rachel, Andrew, John, Thomas and Ulysses.